I’m afraid you’re a very good writer. Well, I'm not, especially not in English as much as in Spanish. But I want to write to you and share random stories, thoughts, feelings, and so many other things. I just want to connect with you. Texting, while cute, instant, and something I love, doesn't quite match up to long conversations or sharing a routine—things that, for me, are very important to truly get to know someone. Letters (this counts as one) don't entirely cover that either. However, letters are the last romantic survivors of communication, which align with the desire of two delirious people getting to know each other, with zero certainty about the outcome they may face.

1.

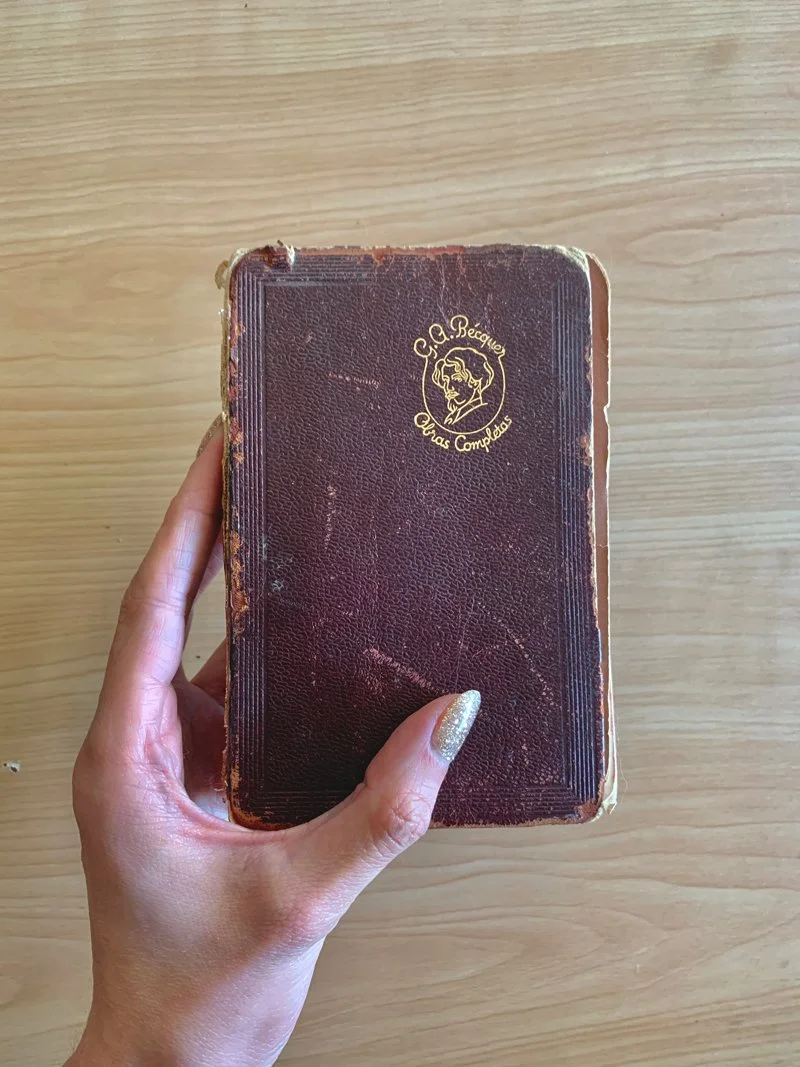

When I was growing up my mother limited our TV time so during summers, if I couldn't swim, I genuinely believed I'd die of boredom. Around the age of 8 or 9, maybe even younger, on one of those eternally tragic dull days I stumbled upon a small, thick book with thin, bible-like pages. It had a dark reddish-chocolate leather cover with a gold badge that read, “G. A. Bécquer, Obras Completas”. It immediately took over me.

I began reading randomly, without any understanding. There were a couple of poems that I liked so much that I memorized them, even though I could reach their meaning even less than I can reach you now (which I hate but that’s a subject for another moment) There were specially two poems that got my attention (english below):

“Yo sé un himno gigante y extraño

que anuncia en la noche del alma una aurora

y estas páginas son de ese himno

cadencias que el aire dilata en las sombras.

Yo quisiera escribirle, del hombre

domando el rebelde mezquino idioma,

con palabras que fuesen a un tiempo

suspiros y risas, colores y notas.

Pero en vano es luchar; que no hay cifra

capaz de encerrarle, y apenas, ¡oh! ¡hermosa!

si teniendo en mis manos las tuyas

podría al oído cantártelo a solas.”

“I know a giant, strange hymn

that proclaims a dawn in the night of the soul

and these pages are cadences of that hymn,

cadences that the air spreads in the shadows.

I would like to write it, taming

man's rebellious and poor language

with words that would be at once

sighs and laughter, colors and tones.

But the struggle is in vain; there is no cipher

capable of containing it; and hardly, oh my beauty!

could I, holding your hands in mine,

softly sing it to you when we were alone.”

What was it about? My 8-year-old brain didn’t know, and frankly, it didn’t care. My 8-year-old spirit compelled me to hold onto those lines for years. When I was 11 or 12, my language teacher discussed modern and romantic poetry from Spain. She described the romantics as these men (yes, totally sexist. I attended a Catholic school where being a wife and having kids was expected of me. What a disappointment I've turned out to be) who possessed such intense inner worlds that even poetry wasn't sufficient for expressing themselves.

I stopped whatever I was doing (school wasn’t a time in my life when I paid attention to classes). She had my full and impatient attention. She then said:

‘Imagine you have to write “Yo sé de un himno gigante”: how immensely frustrating it must have been for a poet whose emotions are so vast they couldn't express them even with words.’

I was in shock.

“I have never felt I’ve been able to truly express myself. I have always misunderstood and rebelled against my existence because it has always felt like a mistake. I’ve always considered myself an outsider that fails to fit in this world while everyone just… are”.

The minute I got back home, I grabbed the book and read most of it.

-I still have it. It sleeps next to me on my nightstand.

2.

When I reached the chapter Cartas literarias a una mujer, I finally grasped the meaning of the second poem I had memorized years ago:

“¿Qué es poesía?, dices mientras clavas

en mí pupila tu pupila azul;

¡Qué es poesía! ¿Y tú me lo preguntas?

Poesía... eres tú.”

«What is poetry?» you ask as you fix

your blue eyes on my eyes.

«What is poetry? And you are asking me?

Poetry… is you.»

… Even at 8 years old I knew it was disgustingly cheese.

Anyway, I began reading the three letters that comprised the chapter, and those letters further explained the annoyingly corny poem. At that moment, I firmly concluded: “Oh, I’m a romantic.” I probably should have added “and an idealist”, but adolescence is inherently idealistic, so it was a given. Little did I know I stayed idealistic, and I'll probably die as one.

3.

Third poem and the inevitable snowball:

Later I found in my house a book of Quevedo’s poetry and couldn’t understand a thing. I honestly didn’t want to put in the effort to understand. I wanted to feel it. Simply feel it. I was on the verge of giving up but then I remembered that my now ex sister’s boyfriend had burned her a CD with music and poetry. I grabbed it and listened to one of the poems: Corazón Coraza by Benedetti.

The verdict was solid:

“I like poetry”

(With a secondary small text just bellow: “I like poetry that I can easily feel”)

I was starving for the romantic written world. I fell in love with Neruda’s 20 poemas de amor y una canción desesperada, devoured Odas Elementales, wrote on my entire bedroom wall Oda al día feliz with big letters and ornaments, got inspired by Rilke’s Cartas a un joven poeta and started flirting with the only Julio Cortázar’s book that were in my house. I need it more.

When summer came my savings were gone: Manuel Montt’s second hand bookstores sponsored the new literature style that entered my life along with Buendía’s family.

That's it.

No climax.

Just a straightforward account the facts about a child who discovered hope and a sense of belonging hidden within a small poetry book.